It was the end of February last year when I published the first in depth report in Italy of ISIS communication techniques. Europe really only noticed the Islamic State and how dangerous it was during the Charlie Hebdo attack. It was at that moment that we realized this was a new phenomena and in the very heart of Europe. Apart from the numerous instant books which came out one after the other to satisfy our (presumed) desire to know, in other countries all of this had already been investigated for some time and in a serious scientific way.

That first work owes and owed much to the years of research and analysis undertaken by many people, particularly in northern Europe and North America. I specifically described it as a “collective” work and cited, among others, Oliver Roy, Dietrich Doner, Eben Moglen, Jeff Pietra, J:M: Berger, Scott Sanford, the generous Will McCants and Clint Watts, the extraordinary Nico Prucha, Rudiger Lohlker, Leah Farrall, Aaron Y Zelin and Peter Neumannal.

The report ended with a quotation by Elham Manea, one of the most courageous and brilliant voices of contemporary Islam who wrote, “ The truth that cannot be denied is that ISIS has studied in our schools, prayed in our mosques, heard our media and the sermons of our religious leaders, read our books and our sources and has followed the fatwa that we have produced. It would be easy to continue to insist that ISIS doesn’t follow the correct precepts of Islam. It would be very easy. Yet, I am convinced that Islam is what we humans make it to be. Every religion can be a message of love or a sword of hatred in the hands of the people who believe in it”.

Since that first report research has gone on and while one group of people has worked to keep track of and analyze the mass of constantly growing propaganda materials, others have concentrated on the study of particular aspects which, with last month’s Paris attacks , have become tragically central and relevant.

This e-book begins with four sections updating ISIS online (but not only) communications in the light of the military and geopolitical developments of recent months and many newly revealed and collected documents.

The next question we posed is relatively simple and based on certain facts: the extraordinary network system of activists and supporters, the existence of a real global network, their knowledge of sophisticated cryptographic systems, the know-how of the Syrian Electronic Army(one of the world’s best hacker networks) and the many connected networks we have tried to map.

We wondered how, propaganda apart, this network could be used for specific purposes such as financing overseas cells, moving money and logistical organization.

The enquiry which follows recounts what I discovered and the significant links which exist with counterfeiting and money laundering at a global level.

As I specified, “ in this public version of my enquiry I have deliberately omitted certain passages. The aim of my investigation is to describe and help to explain a phenomena and a method (one of the methods) of financing and above all of transferring money which is difficult to trace. In no sense do I want it to be a manual, or an invitation to “do it yourself”. The other reason for omission is to protect certain information and active contacts and to preserve the investigative work of those responsible for national and international security who have been given full access to the unabridged results.

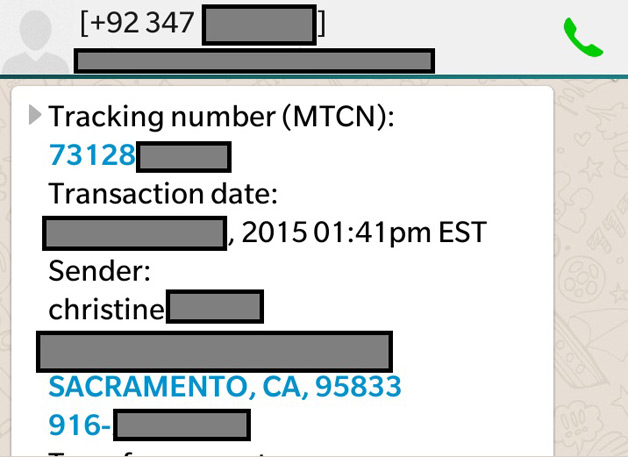

For these reasons the contacts, email exchanges, accounts and phone numbers are not given, just as they are obscured in the images attached.

1. ISIS, from liquid state to territorial organization

2. A battle for fundamentalist identity hegemony

3. Blitzkrieg 2.0

4. Global propaganda

5. ISIS cyber-soldiers networks

6. The connection with the Nigerian scammers network

7. Internet and the financing of ISIS

8. An untraceable money transfer chain

9. The fake identity network

At the beginning of this report, when referring to the conclusion of “ISIS”, the global communication of terror, I quoted Elham Manea when he said“ The truth that cannot be denied is that ISIS has studied in our schools, prayed in our mosques, heard our media and the sermons of our religious leaders, read our books and our sources and has followed the fatwa that we have produced”. It is undeniable that having enrolled Western sympathizers and fighters, ISIS knows our systems, social networks, payment systems and the limits of our research and analysis. It exploits the weaknesses and vulnerabilities of Western societies with a western mindset. We have created a money transfer system which earns commission on the money that immigrants send to their families in poor countries. With first-hand knowledge of how the system works and its limits, they use this system as a weapon against us. We have invented anonymous pre-paid cards and offshore accounts to favor trade but also as a means of exporting currency and tax evasion and they exploit the system’s weaknesses in ways we couldn’t have imagined. We have created social networks aimed at social interaction and membership groups and they, part of the social network generation, have invented a compartmentalized system which evades the social mapping planned by marketers and neutralized by a digital war. (I have written an entire chapter on this with reference to the jihadist article “invading facebook”).

The use of networks by ISIS shows just how wrong the cyber-utopians are and how western legislation based on the liberalist belief in the freedom of internet communications have turned out to be a Trojan horse. The idea that internet “is a weapon for freedom” which could bring down dictatorships and regimes was already undermined during the “Arab Spring” but it continued due to its supporters’ reluctance to admit they were wrong.

Today this idea clearly shows all its contradictions. In reality the idea of internet as an all powerful one-way system to export democracy and freedom was useful to the companies of Silicon Valley when they wanted “few rules and large funds” for the development of their projects. These included anonymous blogging systems to protect democratic activists, direct and private messaging systems and the export of unlimited encryption systems. ISIS is now using these systems with a western mindset against the West.

Not that this should lead people to believe “the web is evil” or “the web should be banned” or that total control could be an effective solution. Exactly the opposite is true. Alongside these distortions in the use of internet, it is often the internet itself which supplies the antidote by providing otherwise impossible solutions, including the use of counter- intelligence. Falling into the banning trap would be like saying that “since kitchen knives can be used in domestic violence, they have to be banned”.

We are afraid of what we do not know, what we are unable to control or dominate, but there are two antidotes to this fear. The first is a solid knowledge of the means and the tool. The other is to be aware that no means or tool is in itself a universal instrument of salvation, just as plain kitchen knives can become an instrument of horror, death and propaganda in the hands of a cutthroat assassin.

However, greater recognition of the potentially dangerous, dark side of new technologies is vital to structural and legislative action against them. Such increased awareness can help us to make cyberspace a safer place with fewer risks. Internet is neither all powerful in the hands of jihadist groups nor in the hands of counter- intelligence forces. It is simply a means for both. Among the countless positive

messages it transmits there are also messages of terror and terrorist recruitment. What really makes a difference are the people and, like all messages, the most effective take root where there is a fertile human terrain. This terrain is made up of segregated poor neighborhoods, subculture, isolation and alienation due to a lack of social integration. Internet did not create these social and cultural ills though it could contribute towards their alleviation. But it is elsewhere that choices and decisions have to made in order to tackle the problems that generate converts and conquest.

Tag: Cyber Jihad

The fake identity network

Clearly I was willing to continue but I didn’t want anyone running any risks. It was too risky to keep on using “my name” so at this point I needed another fake identity. I was hoping that in some way I would be directly supplied with false documents but in a certain sense this turned out to be a vain hope. After a few days I received the details of a contact who sold authentic documents. Basically I had to pay and the

documents would arrive from Cameroon via UPS. Yet again there was no direct way of connecting the transaction, seller or documents to the Caliphate. The entire cost of the operation was financed by a “money transfer” (once again blocked two days later after verifying, as in the first case, that it was highly unlikely the sender had any direct links to ISIS).

My document contact proposed an American passport and a French identity card but I pretended to be a little skeptical, not because I doubted him of course but because the European police carry out such detailed checks and I couldn’t afford to take any risks. So, to convince me of the products’ quality he sent me a video via email showing a newly counterfeited US passport and a security card claiming that these were officially registered documents which would pass any checks.

Inchiesta ISIS from D-ART on Vimeo.

According to an expert who I have worked with in the past, there could be two ways these documents were “registered”. First, the photograph could simply have been replaced on a stolen document which is otherwise original, although this is no longer possible on modern passports. Alternatively, since it would be impossible to penetrate all the national databases, the fake passport could have been inserted into the central database for airport security which contains the entire world’s documents. In his view, and I believe him, this second method would be the most effective, though it would require massive resources and would run a high risk of being intercepted even if some country’s officials were personally involved.

I didn’t check out their quality myself, mainly because in order to receive them I could have risked revealing my true identity in some way. But also because ordering and holding a counterfeit document is a criminal offence. However, although the quality of these documents may not be good enough to pass airport controls, they might easily pass the more superficial checks of a hotel booking, a quick road check or a frontier without computerized systems which are very common in eastern Europe, especially at a time of intense migration. They could also be used to purchase a mobile phone (though in the UK no document is required to buy a sim card), register at an internet point, “demonstrate” the validity of a cloned credit card, send and receive money transfers through MoneyGram or Western Union or receive goods from a delivery service.

An untraceable money transfer chain

To verify these movements, I experimented with some active accounts I have in the jihadist network which I have been using for years to study this phenomena and which therefore have a certain “credibility” in these quarters. In this public version of my research I will intentionally omit certain steps. The aim of my investigation is to describe and help to explain a phenomena and a method (one of the methods) of financing and above all of transferring money which is difficult to trace through a

direct personal experience. In no sense do I want it to be a manual, or an invitation to “do it yourself”. The other reason for omission is to protect certain information and active contacts and to preserve the investigative work of those responsible for national and international security who have been given full access to the unabridged results. For these reasons the contacts, email exchanges, accounts and phone numbers are not given, just as they are obscured in the images attached.

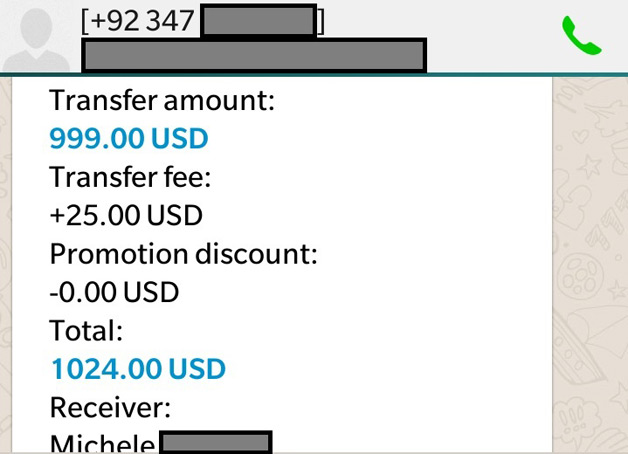

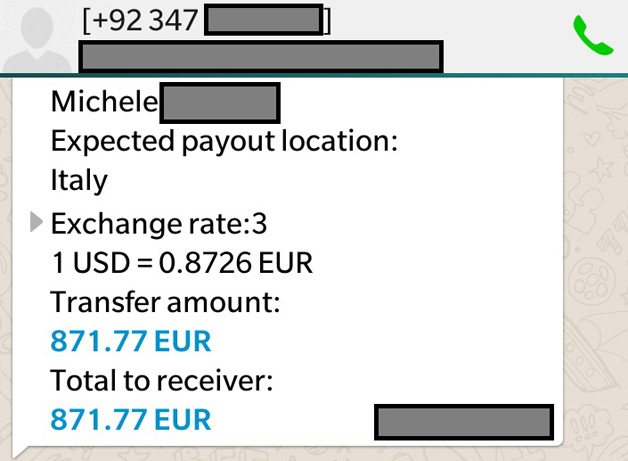

During the summer, as a sympathizer of the Caliphate I made it clear that I was having serious economic problems and consequently had less time to dedicate to activism for the cause. Obviously I was apologetic for this and expressed my deep disappointment. After a few passages between various contacts, I was introduced to someone willing to help me. Obviously personal meetings were out of the question to avoid pointless risks of exposing the network and being discovered. Two days later I received a whatsapp message telling me that I had received 999 dollars from California. This notification came from a friend of the person who had been “willing to help me” with a Pakistani mobile number.

Obviously, after checking that the sum was actually available for withdrawal I had it cancelled as it clearly came from the credit card of a totally innocent person.

This first step of the chain already poses serious issues of traceability.

1. How can this transaction be traced back to an action linked to terrorism?

2. What kind of connection could anyone find between Christine in California, Michele in Italy and the Caliphate?

3. If Michele is using a fake identity, how could he be traced even in the case of cyber crime?

The only trace could be the message which the sender has, almost certainly, cancelled or saved elsewhere and that I, if I were part of a terrorist group or had committed a crime, would equally certainly have cancelled.

As this was for my research, I told them that I was grateful for their help and, as it was more than I needed, offered to send part of the money to another supporter acting as an intermediary. The immediate reply was that this was not necessary because ISIS was great and that wealthy westerners were funding them through their stupidity. However, two days later my original contact sent me some information and asked me if I could send two 50 euro transactions to Pakistan and two to Lithuania, two via MoneyGram and two via Western Union to four separate names.

Internet and the financing of ISIS

The best known and monitored sources of ISIS funding essentially derive from income produced by oil trafficking, kidnapping, the sale of electricity and water, trafficking historical artifacts and the “protection” of industrial plants in certain areas. These resources, which are estimated to amount to between 60 and 90 million dollars a month depending on the month and territory, are used locally to pay for “wages” , arms, ammunition and supplies.

One of the most complex activities for the Caliphate is to convert money into electronic form and transfer it to their overseas networks. There are basically three ways they do this.

Part of the money is deposited by the traffickers/buyers into overseas bank accounts held by third parties. These are often Arab businessmen with legitimate businesses in the West who are sometimes sympathizers but, more often than not, collaborate through fear as a result of threats to family members. This system, though, can only be used for a limited number of operations, frequently for the import/export of arms, because payments through these accounts are effectively traceable.

A report by the Brookings Institution of Washington points to the scarce checks made by Kuwait’s financial institutions as the weak point which allows such “private” funds to reach their destination despite measures taken by the governments of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Qatar to block them.

According to Mahmud Othman, a Kurdish former member of the Baghdad parliament, “one of the reasons the Gulf States allow these private donations is to keep the terrorists as far away from them as possible”. David Phillips, a former senior director of the US State Department now at New York’s Columbus University, affirms that “there are many rich Arabs who play dirty and while their governments claim to be fighting ISIS, they are financing them”. Admiral James Stavridis, former Nato Commander in Chief, calls them “Angel Investors” whose funds “are the seeds from which the jihadist groups grow” and who come from “Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Arab Emirates”.

Some of the private financiers who have been identified, particularly in Qatar, are: Abd al-Rahman al Nuaymi, Salim Hasan Khalifa Rashid al-Kuwari, Abdallah Ghanim Mafuz Muslim al-Khawar, Khalifa Muhammed Turki al-Subaiy and Yusuf Qaradawi. Abd al-Rahman al-Nuaymi is believed to have donated over 600,000 dollars to Al Qaeda in Syria in 2013 and 2 million a month to Al Qaeda in Iraq. According to the US Treasury Department, Salim Hasan Khalifa Rashid al-Kuwari has donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to Al Qaeda in Iraq over the years as has Abdallah Ghanim Mafuz Muslim al-Khawar.

Another part of the money raised from illicit activities is loaded onto “unnamed pre-paid cards” which provide many advantages. They cannot be stolen and can hold large sums in a limited space. Moreover, they are easy to transport and pass on. They don’t have a clearly named card holder so it is very difficult to trace any transactions and as the money is in electronic form numerous payments, even for small amounts, can be made immediately by whoever, anywhere.

The final part of the money raised goes into specific fund-raising activities which exploit social networks through which it is spread out and shared.

Alongside these activities there are the credit-card frauds and phishing activities which effectively turn social networks into recycling networks with dummy or fake

identities offering to receive and re-transfer the money, sometimes in

exchange for a cash payment. This system makes it almost impossible to trace transactions especially as there is often no relation between the senders and recipients.

These are sums of money which apparently have nothing to do with the Caliphate nor any connection with countries or regions under observation. They are simply “country to country” transactions which are frequently put down to “online fraud” without any perceived link with terrorist networks.

The connection with the Nigerian scammers network

We asked ourselves how these networks, apart from providing propaganda, could be used for certain specific activities like financing foreign cells, moving money and logistical organization. The intuition that was a turning point for this enquiry was to look at the connection between ISIS and Boko Haram, the Sunni jihadist movement in northern Nigeria. It was in this link that I tried to find a connection between pro-ISIS digital activists and the universe of the financial network which lies at the root of the so called “Nigerian scams”.

There are wide variations of this scam, but the principle is always more or less the same; a stranger who is having problems with a blocked million dollar bank account , whether it’s an inheritance or to export millions abroad etc. , needs the name of a third party to complete the operation in his name in exchange for a share in the proceeds. This is also known as a 419 scam as 419 is the article of the Nigerian criminal code which punishes this type of fraud.

This kind of scam has evolved over time and in the most up-to-date version could basically be described as a kind of phishing, an internet scam whereby the prowler tries to trick the victim into revealing personal information, banking data or access codes. Although the scam may seem simple on the surface, remaining anonymous and untraceable despite the huge sums of money withdrawn from traceable

electronic systems regarding online current accounts or credit cards is extremely complex.

Essentially, at the very least it requires a good number of people constantly on-line to answer emails and collect the fraudulently gathered data as it comes in. It also requires an in-depth knowledge of the security systems involved in electronic payments and the money needs to be moved quickly by making untraceable.

purchases. Above all, it needs a large number of dummy names who often have more than one fake, but “well made”, identity to receive delivery of goods for example, or to make MoneyGram or Western Union transactions where there are no police experts in false documents. A network of this kind, especially if part of a network of activists and supporters willing to carry out missions and offer logistical support, involves a large number of often untraceable people and is therefore extremely difficult to combat or even map out.

An extraordinary job of this nature was carried out by the AA419 collective (Artists Against 419) which for years dedicated themselves to monitoring, gathering and filing all the emails, Nigerian scams and email /IP addresses. Starting in 2003 their objective was basically to identify the false sites, report them to the hosting servers and get the sites closed down to avoid further fraud. Through this spontaneous and free work they were able to close down over 9,000 sites between 2003 and 2006.

This figure is significant as it underlines the huge dimensions of a network which is estimated to have produced an average of more than 100 million dollars a year. But it is also important to realize just how many human and informatics resources have been dedicated to this criminal activity and how useful the database of those who have tried to fight them can be for researchers.

The ISIS cyber-soldier network

The question we posed is relatively simple and based on certain facts: the extraordinary network system of activists and supporters, the existence of a real global network, their knowledge of sophisticated cryptographic systems and the know-how of the Syrian Electronic Army(one of the world’s best hacker networks).

I wrote about SEA in an article in “Unità” in 2013 when this organization was responsible for embedded attacks on Twitter and other western information sites. SEA, the Syrian Electronic Army, is armed with made-in Russia technology and training (they have a military base there) and exploits servers and connection systems throughout the ex-USSR republics. Officially the group was “autonomous” and financed by Makhlouf, the owner of SyriaTel and Bashar al-Assad’s cousin, who has an office in Dubai.

SEA’s main specialization appears to be mail-phishing software to gain control of PCs and carry out data theft in the constant search for identities to use for counter-information and new attacks. (The full article can be found here)

For a more comprehensive picture, we can be pretty sure that some ex-SEA members (tied to Assad) have joined fronts with another group of hackers known as Al-Nusra Electronic Army which already in 2013 was affiliated with the Al-Nusra rebel front which was presumed to be (and now we know for sure) a branch of Al-Qaeda and now of ISIS. Accused of the defacement of the Syrian Commission on Financial Markets and Securities, it had already operated against the Russian government in March.

Another group is the Aleppo Pirates which since 2013 has been operating in Turkey near the Syrian border. Founded by another ex-SEA member, it works in parallel with yet another group, the Falcons of Damascus.

These numerous cyber groups which are in some ways connected and often coordinated are widespread throughout the area and include the Yemen Hackers, the Muslim Hackers, the Arab Hackers For Free Palestine and the Syrian Hackers School. In addition, there are numerous names which are more like signatures or a mix up of members than really independent groups. The reasons for this are to differentiate the specific actions undertaken but maybe also to give the impression of an even larger number of activists. Examples are, Cyber Jihad Front, Hezbollah Cyber, Cyber Jihad Team, Mujahedeen Team and Memri Jttm, all of which can be traced back to the Cyber Caliphate.

Behind all these names lies a huge network of “indirect” financing which guarantees the availability of networks, technology and connections as well as land lines and some satellite access.

Cyber Jihad

Era fine febbraio dell’anno scorso quando pubblicai in Italia il primo lavoro organico sulla comunicazione dell’ISIS. Dello Stato Islamico e della sua pericolosità ci siamo accorti in Europa con la strage di Charlie Hebdo, ed in quel momento ci siamo accorti che era un fenomeno nuovo ed era nel cuore dell’Europa.

Di tutto questo – al di là degli innumerevoli istant book usciti uno dopo l’altro per riempire la nostra voglia (presunta) di sapere – in altri paesi si stavano occupando da molto tempo. In maniera seria, scientifica, lontani dall’opinionismo dell’ultima ora.

Quel primo lavoro di sintesi deve e doveva molto ad anni di ricerca ed analisi di molte persone, soprattutto in nord europa e nord america. In particolare lo descrissi come un “lavoro collettivo” citando – tra gli altri – Oliver Roy, Dietrich Doner, Eben Moglen, Jeff Pietra, J.M.Berger, Scott Sanford, i generosissimi Will McCants e Clint Watts, lo straordinario Nico Prucha, Rüdiger Lohlker, la brillante Sheera Frenkel, Rainer Hermann, Mehdi Hasan, Elham Manea, Leah Farrall, Aaron Y. Zelin e Peter Neumannal.

Quella ricerca si concludeva con una citazione proprio di Elham Manea, una delle voci più coraggiose e brillanti dell’islam contemporaneo, che ha scritto «La verità che non possiamo negare è che l’Isis ha studiato nelle nostre scuole, ha pregato nelle nostre moschee, ha ascoltato i nostri mezzi di comunicazione e i pulpiti dei nostri religiosi, ha letto i nostri libri e le nostre fonti, e ha seguito le fatwe che abbiamo prodotto». «Sarebbe facile continuare a insistere che l’Isis non rappresenta i corretti precetti dell’islam. Sarebbe molto facile. Ebbene sì, sono convinta che l’islam sia quel che noi, esseri umani, ne facciamo. Ogni religione può essere un messaggio di amore oppure una spada per l’odio nelle mani del popolo che vi crede».

Da quel primo lavoro la ricerca non si è mai interrotta. E mentre un insieme di persone ha lavorato per tenere traccia ed analisi del corposo materiale (costantemente in crescita) di propaganda e diffusione, altri si sono concentrati nella ricerca di alcuni aspetti che – con le stragi di Parigi del mese scorso – sono divenuti tragicamente centrali e attuali.

Questo e-book inizia con un aggiornamento di quattro capitoli sulla comunicazione (non solo) o- line dell’ISIS, alla luce degli sviluppi militari e geopolitici di questi ultimi mesi e dei (molti) documenti nuovi emersi e raccolti.

La domanda successiva che ci siamo posti è abbastanza semplice e partiva da alcuni presupposti: la straordinaria ramificazione di rete degli attivisti e dei supporter, la presenza di un vero e proprio network globale, la conoscenza di sofisticati sistemi di crittografia, il know-how del cd. “esercito elettronico siriano” (una delle migliori reti hacker a livello globale) e di molte reti collegate che abbiamo cercato di mappare.

Ci siamo chiesti come tutta questa rete, oltre che per la propaganda, potesse essere usata per alcune attività specifiche: il finanziamento delle cellule all’estero e lo spostamento di denaro, e l’organizzazione logistica.

L’inchiesta che segue racconta quello che ho trovato e colegamenti iportanti con reti di riciclaggio e contraffazione a livello globale.

Come ho specificato “in questa versione pubblica di questa parte di ricerca volutamente ometterò alcuni passaggi. Questa vuole essere un’inchiesta con l’obiettivo di descrivere e contribuire a spiegare un fenomeno ed un sistema (uno dei sistemi) di finanziamento e soprattutto di spostamento di denaro in modo molto difficilmente rintracciabile attraverso un’esperienza – in questo caso diretta e personale – e non vuole essere un vademecum per nessuno, né un invito “a fare altrettanto”.

Altra ragione delle omissioni è evitare che la divulgazione di certe informazioni, di contatti attivi, potesse in qualsiasi modo e forma minare il lavoro di indagine ed investigativo di chi è preposto a tale compito e per questo motivo il materiale integrale è stato messo a disposizione di soggetti istituzionalmente preposti ad indagini di sicurezza nazionale ed internazionale.

Proprio per questo ho evitato di riportare i contatti diretti, lo scambio di mail, gli account e i numeri di telefono – esattamente come gli stessi sono “oscurati” nelle immagini allegate.

1. ISIS, da stato “liquido” a organizzazione territoriale

2. Una battaglia per l’egemonia identitaria fondamentalista

3. La “guerra lampo” 2.0

4. La propaganda globale

5. Le reti di cyber soldati dell’ISIS

6. Il collegamento con la rete nigeriana

7. La rete e le fonti di finanziamento dell’ISIS

8. Un giro di trasferimento di denaro irrintracciabile

All’inizio di questa inchiesta, riprendendo la conclusione di “Isis, la comunicazione globale del terrore” ho citato Elham Manea che ha detto «La verità che non possiamo negare è che l’Isis ha studiato nelle nostre scuole, ha pregato nelle nostre moschee, ha ascoltato i nostri mezzi di comunicazione e i pulpiti dei nostri religiosi, ha letto i nostri libri e le nostre fonti, e ha seguito le fatwe che abbiamo prodotto».

Quello che non possiamo negare è che avendo arruolato nelle proprie fila combattenti e simpatizzanti occidentali l’ISIS conosce i nostri sistemi, i nostri social network, le nostre reti sociali, i nostri sistemi di pagamento, i limiti che abbiamo nella ricerca e nell’analisi.

Sfrutta le debolezze e le vulnerabilità di un mondo occidentale con la mente e la logica occidentale.

Noi abbiamo creato i sistemi di trasferimento di denaro, e guadagnamo commissioni sulle rimesse che gli immigrati versano alle proprie famiglie in paesi poveri. Loro sfruttano questo sistema – conoscendone paese per paese limiti e soglie e modi di funzionamento – per usarlo come arma.

Noi abbiamo creato carte prepagate anonime e conti offshore per facilitare il commercio elettronico, ma anche talvolta l’esportazione di valuta e l’evasione fiscale. E loro utilizzano questi sistemi come arma, individuandone le vulnerabilità ed usi che non erano stati da noi immaginati.

Noi abbiamo creato i social network, abbiamo immaginato le sfere sociali e i gruppi di appartenenza. Loro conoscono i nostri social network, sono “nati” nell’era social ed hanno immaginato sistemi a camere stagne per evitare la mappatura sociale, immaginata dal marketing, e neutralizzata dalla guerriglia digitale. [a questo ho dedicato un intero capitolo che riprende il documento jihadista “invadere facebook”]

L’uso della rete da parte dell’ISIS è la dimostrazione di quanto i cyber-utipisti sbagliano, e di come le legislazioni occidentali che hanno tenuto conto dei think-tank che proponevano l’onnipotenza libertaria della rete si sono rivelate un boomerang.

L’idea per cui “internet è l’arma della libertà” che avrebbe abbattuto dittature e totalitarismi, già naufragata nelle primavere arabe, ma resistita nonostante tutto soprattutto grazie a una certa pubblicistica che non poteva ammettere di aver sbagliato, oggi mostra concretamente tutti i suoi limiti.

Del resto questa idea di onnipotenza, e di capacità “a senso unico” come arma di esportazione di libertà e democrazia, era utile alle potenti e ricche aziende della Silicon Valley, che richiedevano “poche regole e molti fondi” per sviluppare i propri progetti.

Tra questi, sistemi di blogging anonimi per rendere irrintracciabili gli attivisti democratici, sistemi di messaggistica diretta e privata, esportazione di sistemi di cifratura e criptazione senza limiti.

Oggi l’ISIS usa tutti questi sistemi con una logica occidentale e contro l’occidente.

Questo non ci deve in alcun modo indurre a ritenere che soluzioni manichee per cui “il web è il male” o “il web va vietato” o completamente controllato siano valide ed efficaci.

Semmai il contrario. Perchè accanto a queste distorsioni dell’uso della rete, spesso è proprio la rete a fare da antidoto e ad offire soluzioni anche di intelligence, in altro modo inapplicabili.

Cadere nel facile errore del vietare sarebbe come dire che “dato che i coltelli da cucina possono essere usati per delitti domestici vanno vietati”.

Ci spaventa ciò che non consciamo. Ciò che non possiamo controllare e dominare.

L’antidoto per tutto questo è duplice. Da un parte la conoscenza del mezzo e dello strumento. Dall’altra non considerare alcun mezzo e strumento come salvifico e onnipotente. Proprio come i coltelli da cucina, gli stessi nelle mani di un tagliagole diventano strumenti di morte orrore e propaganada. Pur restando sempre semplici coltelli.

Forse però cominciare a considerare il lato “pericoloso” e le implicazioni “oscure” che gli strumenti delle nuove tecnologie possono avere ci aiuta – molto – sia nel momento decisionale che in quello legislativo, e una maggiore consapevolezza delle possibili implicazioni ed utilizzi ci aiuta a rendere anche il cyber spazio un luogo più sicuro con una ecologia ambientale migliore e con meno rischi.

La rete non è innopetente nelle mani degli jihadisti, esattamente come non lo è nelle mani delle intelligence. Può essere strumento per entrambi. Esattamente come può essere strumento per far passare – tra innumerevoli messaggi positivi – anche alcuni messaggi di terrore e reclutamento terroristico.

La differenza la fanno le persone, e come per tutti i messaggi, anche il più efficace, attecchisce solo laddove c’è un sostrato umano fertile. E questo sostrato è fatto di degrado, di periferie dimenticate, di subcultura, di isolamento, di mancanza di integrazione sociale e di isolamento. Piaghe che la rete non crea, ma che può aiutare semmai a lenire. Ma sono scelte di altro genere e che vanno fatte altrove che possono ridurre al massimo questo terreno fertile che oggi è terreno di proselitismo e conquista.

La rete delle false identità

La mia disponibilità a continuare ovviamente c’era ma nessuno della rete avrebbe dovuto correre rischi. A questo punto mi servivano altre identità. Troppo rischioso usare “sempre la mia” e fare tanti movimenti.

La mia speranza è che in qualche modo mi facessero avere in maniera diretta dei documenti falsi comunque credibili. Speranza vana almeno sino a un certo punto.

Ricevo dopo alcuni giorni i riferimenti di un contatto che vendeva documenti autentici.

La sintesi della questione era che dovevo pagare io e che i documenti mi sarebbero arrivati, questa volta dal Cameroon, direttamente via UPS.

Ancora una volta nessun modo di collegare transazione, venditore, documenti, in forma diretta al califfato.

Il costo dell’operazione viene interamente finanziato da un “money transfert” [anche questo bloccato dopo due giorni e dopo aver verificato che il mittente – come la prima volta – difficilmente poteva avere legami diretti con l’ISIS].

Il mio contatto per i documenti mi propone un passaporto americano e una carta di identità francese e dato il mio scetticismo (non dubito di lui, ma in Europa la polizia fa controlli approfonditi e non potevo rischiare) per mostrarmi la bontà del prodotto mi manda via mail un video con un passaporto americano ed una tessera della sicurezza appena contraffatti.

Inchiesta ISIS from D-ART on Vimeo.

Sostengono che questi documenti siano anche “registrati” e passino quindi i relativi controlli. Secondo un esperto con cui ho collaborato i sistemi di questa registrazione potrebbero essere due: la

semplice sostituzione della fotografia su documenti rubati e i cui dati quindi coincidono (non fattibile ad esempio per passaporti di ultima generazione), oppure, non potendo fisicamente penetrare tutti i database di tutti gli Stati, probabilmente inserendo i documenti contraffatti nel database centrale della sicurezza aeroportuale, in cui confluiscono i documenti di tutto il mondo. La seconda ipotesi – mi spiega, e mi fido – sarebbe quella più efficace, anche se a suo dire richiederebbe risorse impressionanti e sarebbe a forte rischio di rilevazione, anche in casi di complicità istituzionali di alcuni alti funzionari di alcuni Paesi.

Io non ho fatto una prova diretta, innanzitutto perchè spedendomi il documento la mia vera identità in vario modo sarebbe stata rivelata. Non l’ho fatta anche perchè il solo ordinare un documento falso e detenerlo è in sé reato.

Di certo però la qualità dei documenti di cui parliamo, se non basta a passare un controllo aeroportuale, facilmente può ingannare in caso di prenotazione alberghiera, di un veloce controllo stradale o in passaggi di frontiera non informatizzati (e ad est dell’Europa, specie in tempi di migrazioni intense, ce ne sono moltissimi), dell’acquisto di un utenza cellulare (addirittura in Inghilterra è possibile acquistare sim card senza il rilascio di alcun documento), o per la registrazione in un internet point, e nel caso occorresse ricevere denaro in un centro MoneyGram o WesternUnion o per “accompagnare” una carta di credito clonata o farsi consegnare merce spedita a mezzo corriere.

La rete e le fonti di finanziamento dell’ISIS

Le fonti di finanziamento note e monitorate dell’ISIS derivano essenzialmente dai proventi del contrabbando di petrolio, dei sequestri, della vendita di energia elettrica ed acqua, del contrabbando di manufatti antichi, della “protezione” di installazioni industriali in determinate aree.

Queste risorse – che vengono complessivamente stimate a seconda dei mesi e della estensione territoriale in una forbice tra i 60 e i 90 milioni di dollari mensili – vengono usate “in loco”, per il pagamento di “stipendi”, armi, munizioni, approvviggionamenti.

Un’attività complessa per il califfato deriva dalla necessità di convertire in forma elettronica il denaro e di farlo pervenire alla rete estera.

Ciò avviene sostanzialmente attraverso tre sistemi.

Una parte del denaro viene depositata dai trafficanti/acquirenti esteri in conti intestati a prestanome, spesso uomini di affari arabi operanti legittimamente in paesi occidentali, e altrettanto spesso coinvolti per paura, con minacce a familiari, quando non direttamente simpatizzanti.

Si tratta di somme “a dispozione” di poche operazioni, spesso di import export di armi, perchè eventuali pagamenti da quei conti sono comunque rintracciabili.

Un rapporto della «Brookings Institution» di Washington indica nei carenti controlli delle istituzioni finanziarie del Kuwait il vulnus che consente a tali fondi «privati» di arrivare a destinazione «nonostante i provvedimenti dei governi kuwaitiano, saudita e qatarino per bloccarli».

Secondo Mahmud Othman, ex deputato curdo a Baghdad «Una delle ragioni per cui i Paesi del Golfo consentono tali donazioni private è per tenere questi terroristi lontani il più possibile da loro». David Phillips, ex alto funzionario del Dipartimento di Stato Usa ora alla Columbia University di New York, assicura: «Sono molti i ricchi arabi che giocano sporco, i loro governi affermano di combattere Isis mentre loro lo finanziano». L’ammiraglio James Stavridis, ex comandante supremo della Nato, li chiama «angeli investitori» i cui fondi «sono semi da cui germogliano i gruppi jihadisti» ed arrivano da «Arabia Saudita, Qatar ed Emirati».

Tra i finanziatori privati diretti sono stati individuati in particolare in Qatar Abd al-Rahman al- Nuaymi, Salim Hasan Khalifa Rashid al-Kuwari, Abdallah Ghanim Mafuz Muslim al-Khawar, Khalifa Muhammad Turki al-Subaiy, Yusuf Qaradawi. Abd al-Rahman al-Nuaymi avrebbe donato oltre 600 mila dollari nel 2013 ad Al Quaeda in Siria e due milioni al mese ad Al Quaeda in Iraq. Salim Hasan Khalifa Rashid al-Kuwari – come afferma dipartimento del tesoro americano – avrebbe donato avrebbe donato centinaia di migliaia di dollari ad Al Quaeda in Iran nel corso degli anni e così anche Abdallah Ghanim Mafuz Muslim al-Khawar.

Una parte del denaro del pagamento delle attività precedentemente descritte viene invece consegnato in “carte prepagate anonime” che offrono enormi vantaggi. Non possono essere rubate, possono contenere cifre considerevoli in uno spazio molto ridotto e sono facilmente trasportabili e trasmissibili. Non hanno un titolare ben preciso, il che significa che non si ha nemmeno un punto di partenza o di arrivo per rintracciarne le transazioni. Rendono il denaro elettronico, consentendo trasferimenti – anche numerosissimi per importi molto modesti – praticamente in tempo reale a chiunque e ovunque.

Una terza parte di risorse vengono drenate attraverso tool di fundraising specifici che sfruttano i social network per essere diffusi e venire condivisi.

A queste attività vengono affiancate le frodi su carte di credito, attività di phishing, trasformando la rete sociale in una vera e propria rete di riciclaggio con prestanome che si impegnano a ricevere denaro e ritrasferire denaro (qualche volta trattenendo una cifra in contanti) rendendo la tracciabilità delle transazioni quasi impossibile, anche per la mancanza assoluta di coerenza tra mittente e destinario e suo utilizzo.

Cifre che non hanno niente a che vedere direttamente con il califfato, che non hanno alcuna origine in paesi o aree o regioni sotto osservazione: transazioni “estero su estero” che nella maggior parte dei casi vengono archiviate come “frodi informatiche” senza alcun legame percepibile con la rete terroristica.

Il collegamento con la rete nigeriana

Ci siamo chiesti come tutta questa rete, oltre che per la propaganda, potesse essere usata per alcune attività specifiche: il finanziamento delle cellule all’estero e lo spostamento di denaro, e l’organizzazione logistica.

L’intuizione che ha dato una svolta a questa ricerca è stata il considerare la vicinanza tra ISIS e Bokoharam, il movimento jihadista-sunnita presentre nel nord della Nigeria, e da qui ho cercato i collegamenti tra attivisti digitali filo ISIS e l’universo esperienziale della rete finanziaria che ha originato (appunto) le cd. “truffe nigeriane”.

Esistono numerose varianti di questa truffa ma il principio è più o meno sempre lo stesso: uno sconosciuto non riesce a sbloccare un conto in banca di milioni di dollari (o un’eredità, o vuole esportare milioni all’estero etc); essendo lui un personaggio noto, avrebbe bisogno di un prestanome discreto che compia l’operazione al suo posto. Invita così alcuni utenti concedendo loro questa possibilità in cambio della promessa di ottenere una fetta del bottino. La truffa è chiamata anche 419scam (419 è l’articolo del codice penale nigeriano che punisce questo genere di truffa).

Quel modello di truffa – variamente declinata – è stata col tempo affinata e nella sua versione 2.0 può venire a vario titolo descritta come una sostanziale attività di phishing (un tipo di truffa effettuata su Internet attraverso la quale un malintenzionato cerca di ingannare la vittima convincendola a fornire informazioni personali, dati finanziari o codici di accesso).

Se la truffa in sé può apparire semplice in termini di realizzazione, in realtà mantenere l’anonimato ed essere irrintracciabili, nonostante siano state prelevate somme di denaro attraverso sistemi elettronici tracciati (conti correnti online e carte di credito) è estremamente complesso. Semplificando il tutto, è necessario come minimo avere un certo numero di persone sempre online per rispondere alle mail e raccogliere i dati fraudolentemente ottenuti in tempo quasi reale, è necessario disporre di una conoscenza ampia dei sistemi di controllo e sicurezza delle transazioni elettroniche, è necessario spostare rapidamente il denaro compiendo acquisti non tracciabili e soprattutto avere una vasta rete di prestanome, spesso con più di una identità falsa ma “fatta bene”, ad esempio per ricevere merci a mezzo corriere o farsi riconoscere in MoneyGram o in un punto WesternUnion (per citare i più diffusi), dove di certo non ci sono poliziotti esperti di contraffazione di documenti ed identità.

Una rete di questo tipo, soprattutto se integrata con una rete di supporter ed attivisti “disponibili” a compiere azioni di supporto logistico, oltre che per vastità certamente in termini di rintracciabilità è estremamente difficile da abbattere, ed anche solo da mappare.

Un lavoro straordinario in tal senso lo dobbiamo al collettivo AA419 (artists against 419) che per anni si è occupato di monitorare, raccogliere, archiviare tutte le mail e le truffe nigeriane e indirizzi mail ed ip. La sua attività, iniziata nel 2003, era quella sostanzialmente di identificare i siti fasulli, segnalarli ai servizi di hosting e far oscurare il sito per evitare il protrarsi delle truffe.

Un’attività gratuita e spontanea che ha fatto chiudere oltre 9.000 siti tra il 2003 e il 2006.

Questo dato è importante per renderci conto di quanto vasta sia una rete che si stima abbia generato frodi per una media di 100 milioni di dollari all’anno. Ma è anche importante per comprendere quante risorse umane ed informatiche siano state messe in piedi per generare questo genere di attività criminale e quanto importante sia per chi fa ricerca il metabase messo in piedi da chi ha cercato di contrastare questo fenomeno in rete.